America’s lost century and the rise of a new global order

There is an overwhelming sense that the 'greatest generation' of US leadership and authority is irrevocably declining

America’s lost century and the rise of a new global order

There is an overwhelming sense that the 'greatest generation' of US leadership and authority is irrevocably declining

January 05, 2025

This article originally appeared in INews

Looking forward by looking backward has never been a prescription for success, not for individuals or nations.

Yet president-elect Donald Trump promises to make “America Great Again” by restoring an idyllic, if imagined, past, when American power was unchallenged, and the dollar ruled the world.

He offers to end the war in Ukraine in a week or a month, counting on an invented “bromance” with Vladimir Putin to seal a deal.

He dreams of a Europe that pays its own way for defence, promising to walk if his terms are not met.

He vows a reprise of his stillborn “Deal of the Century” – a peace agreement between Israel and Palestine – which he pledges will rise from the ashes of Gaza.

He promises to “build a wall” and deport tens of thousands of migrants fleeing failed states across three continents – migrants whose only crime is their belief that the United States offers their best chance for a prosperous future.

“You (migrants) better start packing,” declared Trump’s border tsar recently.

The newly elected president imagines a renaissance of American manufacturing energised by a Trump Tariff on goods that can be produced more cheaply and efficiently by friends in Europe and Mexico, or competitors in Asia.

Trump threatens to fire thousands of federal workers, from the Department of Education to the Pentagon, whose absence, he claims, will allow citizens to get on with the business of making business, unfettered by environmental or “woke” considerations.

In their place, Trump envisions a federal bureaucracy permanently dispatched from headquarters in Washington to the hinterlands, staffed by Trump loyalists.

The president-elect is certainly not the first to mine electoral gold from the promise of a better American future.

America has always been a dream machine. Unsullied by the malignant corruption of the Old World, the arsenal of democracy and economic rehabilitation, the United States, in the mid-twentieth century, stood astride war-ravaged and enfeebled dynasties in Asia, holding out the promise of a better future to nations and peoples prostrate from half a century of conflict.

Americans were not alone in seeing themselves in this heroic, if manufactured, image. Hollywood and war-weary audiences around the world hungered for brave, selfless, and patriotic Americans like those portrayed in 12 O’Clock High, Casablanca, and The Best Years of Our Lives.

And indeed, there was more than an element of truth to the awe with which broken European societies viewed the brash, naïve, and good-natured Americans, who wielded their all-but-unchallenged influence with a smile.

In this America, there was no menace, as there is today – when the crowd bellows “USA! USA!” on almost every public occasion – no aggressive assertion of entitlement. The Marshall Plan, which put Europe on the road to post-war recovery, was a faintly disinterested, almost benevolent exercise of American power.

There was room for everyone in the post-war world order that Washington built. Well, almost everyone. Russia, China, and much of the Third World languished.

Bretton Woods and free trade, the UN and its Security Council – the global institutions championed and funded by the United States – both reflected and advanced the global reach of American leadership.

Technology was an American monopoly, and so were its stars. Rocky the Flying Squirrel, with his sidekick Bullwinkle, always outwitted the comically inept KGB spies Natasha and Boris Badenov.

The Cold War was an almost tame, defanged, and at times humorous repudiation of the wars that had debilitated the power of dynasties and rulers in Europe and Asia. At the UN, Khrushchev, enraged by criticism of Soviet policies in Eastern Europe, banged his shoe on the lectern – a histrionic demand for attention.

The mirage of the missile gap, used to such great effect by American politicians and their military-industrial complex in the 50s, was made real by Sputnik, empowering Kennedy’s promise to beat the Russians to the moon by 1970. The achievement was indeed a symbol of American superiority, but it was also celebrated by the world.

Yet the destruction of the planet on a scale that the US bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki only hinted at made the Cold War alarmingly real. The threatening, unnerving spectre of a new, far more lethal holocaust burned itself into the consciousness of a generation.

To address this threat, détente among superpower rivals became the pillar of the framework of agreements and understandings fashioned during the 70s and 80s. ABM, SALT I and II, MBFR, and other institutions were prominent among agreements meant to reduce, if not banish, the threat of nuclear war.

This neat world is no more. The American century still dominates, but there is an overwhelming sense that the “greatest generation” of American leadership and authority is irrevocably declining.

China, which little more than a century ago had the largest Gross National Product (GNP) of any country, has finally discovered a way to escape endemic instability and poverty. Deng Xiaoping’s declaration that “to get rich is glorious” set China on a course that is transforming not just China but the entire world, posing a challenge to American power far more potent than anything conjured in Moscow during the Cold War.

In one generation, China raised half a billion people out of poverty – a historic feat that established the scale of achievements that China’s awakening is still producing. These achievements make the People’s Republic a lodestar for the Global South and many others disaffected by the shortcomings of American leadership.

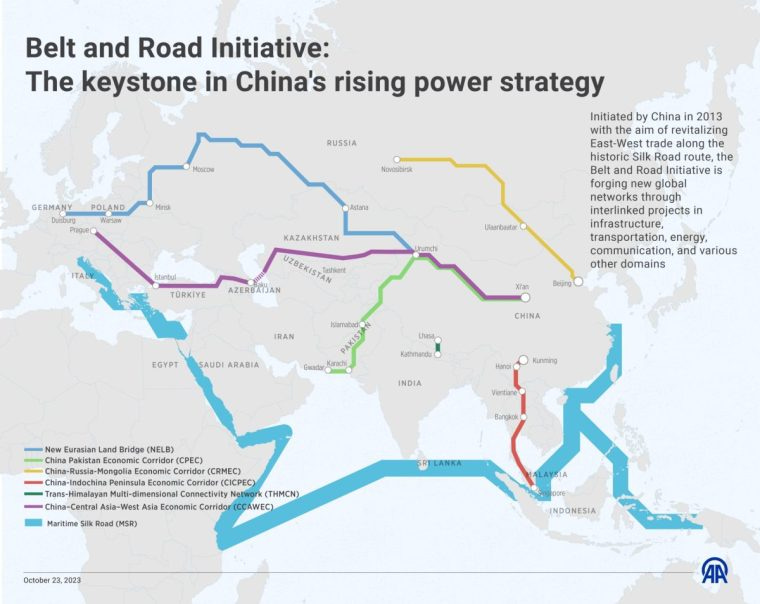

British textiles and American manufactures once symbolised the international reach of the West’s power. Today, and notwithstanding American efforts, it is China and its associated manufacturers throughout Asia and beyond that are supplying the demands of an expanding international marketplace. China’s growing economic power is reflected in myriad ways – from its dominance of green economy technologies and electric vehicle (EVs )to steel production, consumer goods, and a campaign of infrastructure modernisation that puts America’s creaking transport network – whose interstate highways were once a marvel of American achievement – to shame. Billions have been spent – from Sri Lanka to Peru – on infrastructure “Belt and Road” projects, the heart of China’s strategy to reconfigure international transport and development routes to serve its own economic and strategic interests.

Two decades of economic competition with China have all but destroyed the link between American economic power and the institutions it once championed to encourage free trade. Trump supports this estrangement from these global institutions, like the World Trade Organisation. Today it is China, rather than Washington, that laments the costs of “reshoring” industries like computer chip manufacturing. More broadly, American leaders – Democrats and Republicans alike – have embraced tariffs, economic sanctions, and nativism with an enthusiasm not witnessed since the disastrous “beggar thy neighbour” trade and immigration policies of the 30s.

Trump believes that “the global trading system of the late 20th century is not sustainable,” notes Oren Cass, founder of American Compass, a conservative think tank. “The endgame here isn’t some kind of negotiation where we all get back to 1995,” when the World Trade Organisation came into force. Rather, it’s a “fundamental rebalancing.”

In other words, “scrap it.”

And what about the views of the titans of American economic power, whose coffers have been filled by collaborating with the internationalism that long defined US economic power?

Capital, it seems, is a coward. From Russia to China, American firms are “derisking” – deferring to Washington’s trade-phobic, mercantilist diktat. With varying degrees of enthusiasm, they are withdrawing from markets at Washington’s behest and are now among the strongest cheerleaders of the multi-billion-dollar subsidy of favoured US-based industries both parties believe are necessary to remake America’s twenty-first-century economy.

Not surprisingly, there is a growing view internationally that there is less opportunity in the system that American political and economic elites are embracing, than there is in the emerging, expanding Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) coalition.

The 16th Brics summit, just held in Kazakhstan, is the most recent indicator of both the evolving power of the coalitions aiming at challenging the US-led system and the growing attraction of China’s rise as the (non-American) wave of the future. Beijing is today emerging as the champion of a system of economic relations that once powered the extraordinary achievements of postwar America. In a word: “sovereignty and free trade” – but with Chinese characteristics.

One key indicator of BRICS’ dynamism is the entry of six new countries – Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE – expanding membership from key members of the Global South. The expansion of BRICS reflects disaffection with core Western institutions like the UNSC and a broader interest in fashioning a multipolar successor to American pre-eminence.

The Kazan Declaration, adopted at the summit, emphasised BRICS’ dedication to multilateralism and proposed reforms for global governance, including the United Nations and the IMF. In line with reducing dependency on the US dollar, BRICS discussed advancing a common currency and blockchain-based payment systems to foster economic independence within the bloc.

None of this will happen overnight, not even in a generation – but Rome was not built in a day.

Geoffrey Aronson writes about Middle East affairs. He consults with a variety of public and private institutions dealing with regional political, security, and development issues. He has advised the World Bank on Israel’s disengagement and has worked for the European Union Coordinating Office for the Palestinian Police Support mission to the West Bank and Gaza